Database Scaling Patterns

Different approaches for managing database growth

When we build applications, we typically start simple - a single database instance serves our needs well. I’ve seen many projects begin with a basic PostgreSQL or MySQL setup, containerized for convenience. This approach works perfectly fine for many applications, and truth be told, most applications won’t outgrow this setup.

But what happens when you do hit those scaling limits? In this article, I’ll explore several patterns that have worked successfully for me to handle database growth. While I’ll use PostgreSQL in my examples (as it’s what I work with most), these patterns are broadly applicable across different database technologies.

The Index Pattern

The most fundamental pattern for improving query performance is Indexing. At its core, an index is a data structure that provides a fast path to rows in a table.

Creating an Index in Postgres

CREATE INDEX name

ON table

USING BTREE (column);

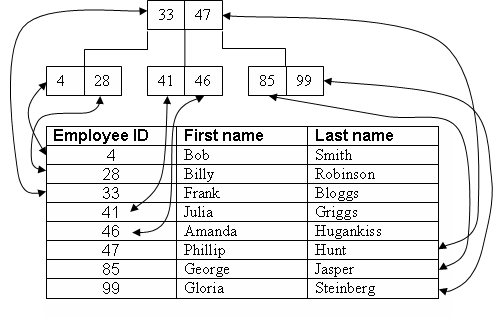

Whilst there are different types of indexes, the most common (and default) implementation is the B-Tree index, which maintains data in a sorted tree structure. Think of it like a well-organized library with numbered shelves. Instead of checking every book one by one (like a full table scan), the library has a series of signs at different levels:

- Main floor sign: “Books 1-1000 left wing, 1001-2000 right wing”

- Wing signs: “Books 1-500 first aisle, 501-1000 second aisle”

- Aisle signs: “Books 1-100 top shelf, 101-200 middle shelf…”

When you want to find book #200, you:

- Check main sign -> go left wing

- Check wing sign -> go first aisle

- Check aisle sign -> go middle shelf

- Find #200 in that section

This hierarchical organization means you can quickly find any book number, including ranges (like “all books between 350-400”) without checking every single book. You’re making just a few decisions at each level to narrow down your search area, which is why it’s logarithmic - O(log n) - rather than linear - O(n).

The following is an illustration from Wikipedia:

When to Use It

The Index Pattern is most effective when you have specific columns that are frequently used in WHERE clauses. It is sometimes also effective on JOIN conditions (although not necessarily). Query performance, especially for larger tables, can be significantly improved simply by adding the right indexes.

Trade-offs

The main trade-off with indexes is write performance. Each index needs to be updated whenever you modify the underlying data. So of course, be selective about indexing - don’t just index everything.

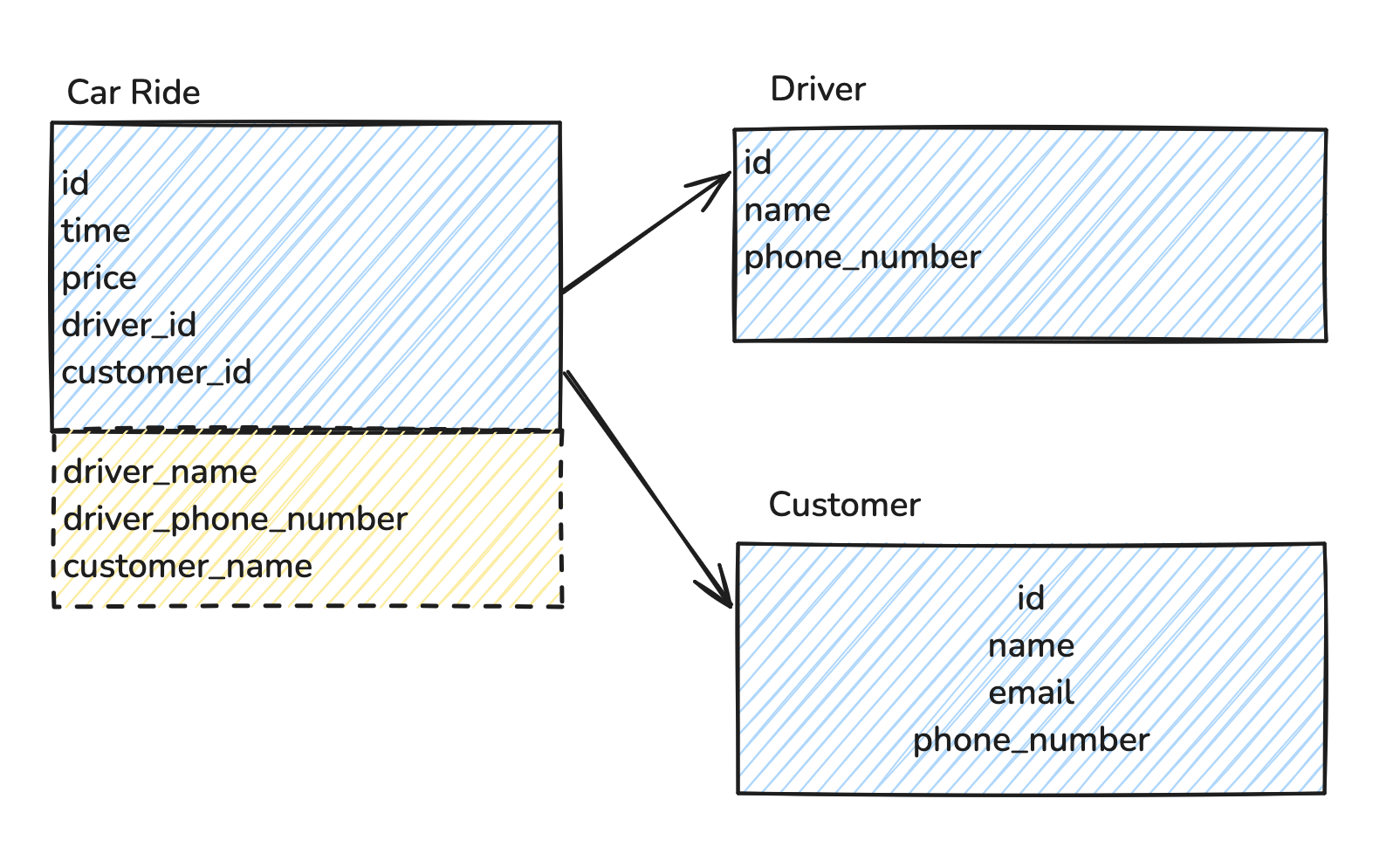

The Denormalization Pattern

While database normalization is generally good practice, sometimes we need to deliberately denormalize for performance. Consider the example below. Assuming that we show a table for all our customers with their car rides, and the table will contain driver information and the name they booked under, it may make sense to add this data to the CarRide table, making all data readily available with a filter.

When to Use It

Consider this pattern when:

- You have frequently-executed queries that require expensive joins

- The joined data changes infrequently

- Query performance is more critical than storage efficiency

Trade-offs

The main complexity comes from maintaining data consistency. When you update the source data, you need to ensure all denormalized copies are updated too. This isn’t just a technical challenge - it’s an organizational one, as teams need to be aware of these dependencies.

The Caching Pattern

The Caching Pattern introduces a fast, intermediate storage layer between your application and database. Redis is a popular choice for this pattern, though in-memory application caches can work too. Caching may be an alternative to denormalization in the example above.

When to Use It

This pattern shines when:

- The same data is repeatedly requested

- Data can be slightly stale without causing problems

- You need to reduce database load during high-traffic periods

Trade-offs

Cache invalidation is the classic challenge here. Remember Phil Karltons? “There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.”

The Partitioning Pattern

Partitioning is about breaking a large table into smaller, more manageable pieces. There are two main variants:

Vertical Partitioning

This splits tables by columns. While PostgreSQL doesn’t directly support this, you can achieve it through careful normalization. So when should we normalize and when should we denormalize? Look at your most expensive queries. If only a few columns are required from a table, normalizing your tables (and having the rare JOIN on occassion) will be more performant for your application.

Horizontal Partitioning

This splits tables by rows, usually based on a partition key. PostgreSQL supports this natively:

CREATE TABLE user (

user_id int not null,

created date not null,

age int,

name varchar(255)

) PARTITION BY RANGE (age);

The Sharding Pattern

Sharding takes partitioning to the next level by distributing data across multiple servers. While PostgreSQL doesn’t provide this out-of-box, tools like Citus make it possible.

When to Use It

Consider sharding when:

- You’ve exceeded the capacity of a single server

- Your data can be cleanly partitioned by a shard key

- You need horizontal scalability

Trade-offs

Sharding adds significant complexity to your system. Cross-shard queries become challenging, and you need to carefully consider your sharding strategy.

The Vertical Scaling Pattern

Sometimes the simplest solution is to just add more resources to your existing database server. More often then not this is one of the first solutions to go to, before taking a look at more complex ones.

Trade-offs

While simple to implement, this pattern has clear limitations:

- Cost increases can be substantial

- Hardware limits eventually become a barrier

- You still have a single point of failure

The Materialized View Pattern

This pattern involves pre-computing complex queries and storing the results. It’s particularly useful for reporting and analytics scenarios where real-time data isn’t critical.

When to Use It

Consider this pattern when:

- You have complex queries that run frequently

- The underlying data changes infrequently

- You can tolerate some data staleness

Trade-offs

The main challenge is managing the refresh cycle - when to update the materialized view and how to handle the load during updates.

Conclusion

Each of these patterns has its place in your database scaling toolkit. The key is understanding their trade-offs and choosing the right combination for your specific needs. In my experience, successful database scaling usually involves applying several of these patterns together, guided by careful observation of your application’s actual usage patterns.